What King & Conqueror covers

One year can flip a country on its head. The BBC’s new historical drama King & Conqueror goes straight to the storm at the heart of 1066, tracking how rival claims and hard bargains pushed England toward a showdown that still shapes its identity. Created by Michael Robert Johnson for BBC One, the eight-part series premiered on August 24, 2025, and aims to make the stakes of that volatile decade feel immediate rather than museum-distant.

The frame is broad by design. The opening chapter reaches back to the coronation of Edward the Confessor in 1043, a choice that sets the story well before arrows fly and banners fall. From there, the show builds the rivalry between Harold Godwinson and William, Duke of Normandy, as a political chess match where every oath, marriage, and rumor matters. Armies and armor are here, sure, but the engine is legitimacy—who can claim the right to rule and get enough people to believe it?

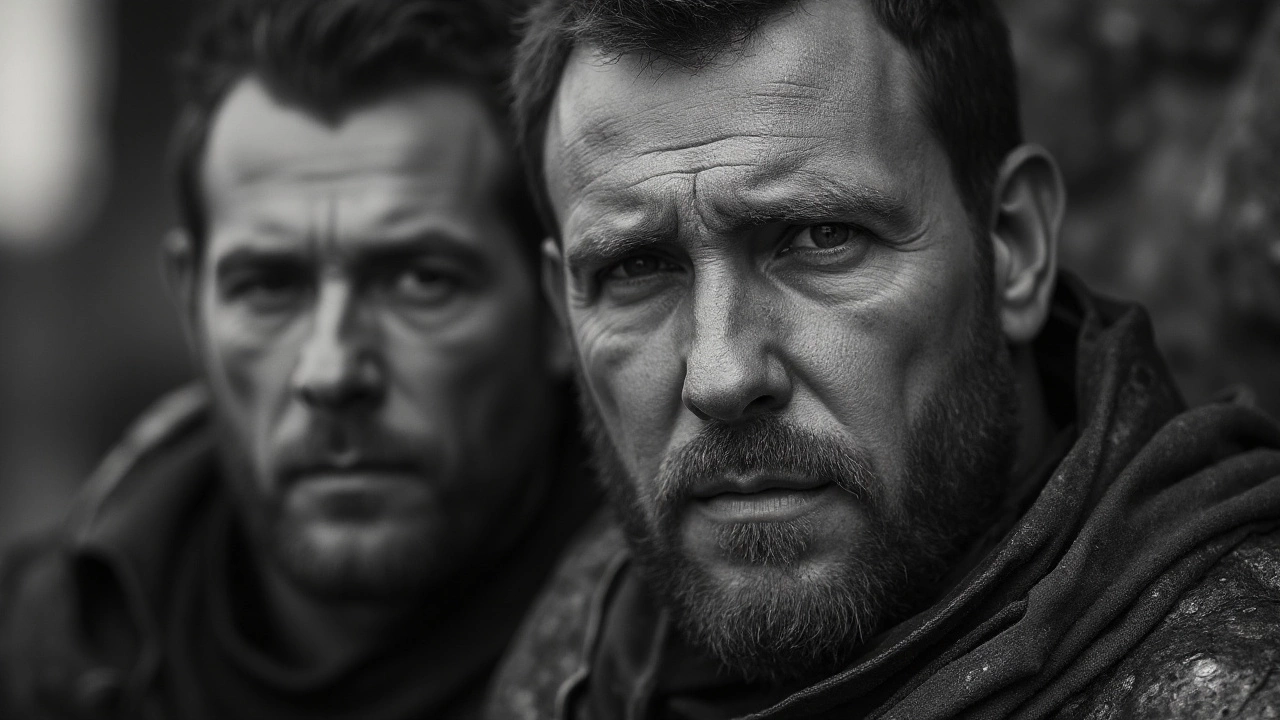

James Norton steps into Harold’s boots, playing the last Anglo-Saxon king not as a saint or a villain but as a man shouldering a web of family loyalties and shifting alliances. Across the Channel, Nikolaj Coster-Waldau’s William is sharp and relentless, a strategist who understands that power is part law, part theater, and part fear. The series wants both men to feel human: ambitious, flawed, and watchful. When they eventually face off, it’s not just steel on a field—it’s years of positioning crashing together.

The show also gives real space to the women whose influence is often written off as background. Clémence Poésy’s Matilda of Flanders isn’t a decorative presence; she’s a political actor in her own right, shaping William’s image and alliances. Emily Beecham plays Edith, Harold’s partner, caught between personal bonds and the brutal arithmetic of succession. The narrative weaves in Emma of Normandy, Edith the Fair, and Edith of Wessex (renamed Gunhild in the drama), underlining how marriage, wardship, and courtly favor could tilt the map as surely as spears.

Historical debates aren’t avoided; they’re brought to the front. The most famous example is the “arrow in the eye” question at Hastings, a detail many viewers know from the Bayeux Tapestry. The series plays with that uncertainty rather than pretending it’s settled, and that’s to its credit. Where it risks overreach, say experts, is in its treatment of Harald Hardrada, the Norwegian king and third claimant. Some historians have pushed back at the rough-edged, “brutish Viking” shorthand. It’s a reminder that all dramatizations choose a lens, and sometimes that lens narrows the view.

Edward the Confessor, portrayed here by Eddie Marsan, is another flashpoint. On screen, he’s more puppet than king, which amps up the palace intrigue but doesn’t match every reading of the records. The writing clearly prefers the tension of a court controlled by baronial power, and that choice sets the tone: this is a saga about will and influence, not just banners and bloodlines.

On production, the series leans into tactile detail—heavy textiles, practical mail and helmets, smoky halls, mud underfoot. Battles are staged with scale, but the camera keeps circling back to faces: counselors whispering in alcoves, family councils that feel like hostage negotiations, and quiet moments when characters realize the cost of the moves they’ve made. It’s less sermon, more pressure cooker.

Early reaction? Mixed. As of now, the show holds a 5.9/10 on IMDb from 416 user ratings. Some viewers appreciate the sweep, the performances, and the way it treats propaganda as a weapon. Others want tighter accuracy, fewer shortcuts, and a more expansive take on figures like Hardrada and Edward. That divide is common with historical epics: the closer a series treads to classrooms and museums, the louder the debate gets.

What the series does land is the sense of a continent in flux. Normandy, England, and Scandinavia sit on a seesaw, and a strand tugged in one court snaps a rope in another. If you’re watching for politics, it’s rich; if you’re here for battles, the show builds toward them rather than spending them early. Eight episodes give it room to set traps, walk characters into corners, and make the final clash feel earned.

Cast, characters, and early reception

This is an international ensemble, and it shows. The leads are headline names, but the bench is deep with faces who bring muscle and texture to the world. Here’s how the core lineup breaks down.

- James Norton as Harold Godwinson — England’s last Anglo-Saxon king, navigating power at home and pressure from abroad.

- Nikolaj Coster-Waldau as William of Normandy — a calculating duke who turns claim into campaign.

- Emily Beecham as Edith — Harold’s wife, whose loyalties and losses carry real weight.

- Clémence Poésy as Matilda of Flanders — William’s partner in politics and image-making.

The supporting cast fills out courts, war councils, and rival families:

- Geoff Bell as Godwin

- Clare Holman as Gytha

- Ingvar Sigurdsson as Fitzosbern

- Elliot Cowan as Sweyn

- Luther Ford as Tostig

- Bo Bragason as Queen Gunhild

- Bjarne Henriksen as Earl Siward

- Jean-Marc Barr as Henry I of France

- Léo Legrand as Odo

- Juliet Stevenson as Lady Emma

- Eddie Marsan as King Edward

- Oliver Masucci as Baldwin

And the wider roster gives the political map its breadth:

- Elander Moore as Morcar

- Calum Sivyer as Tallifer

- Vigdís Hrefna Pálsdóttir as Cécile

- Jason Forbes as Thane Thomas

- Joakim Nätterqvist as Thorolf

- Indy Lewis as Margaret

- Sveinn Geirsson as Baron Montgomery

- Valdimar Örn Flygenring as Baron George

- Björgvin Franz Gíslason as Baron Richard

- Ines Asserson as Judith

- Sveinn Ólafur Gunnarsson as Hardrada

- Stormur Jón Kormákur Baltasarsson as Alain of Brittany

- Þorsteinn Bachmann as Baron of Brittany

Performance-wise, the series leans into contrasts. Norton’s Harold reads as burdened by duty but quick to act, a man who believes legitimacy can be built at home. Coster-Waldau’s William is all iron and memory—he never forgets a promise made or an insult given, and the camera often finds him in moments where calculation looks almost like calm.

The women’s arcs are not window dressing. Poésy’s Matilda understands presentation as power; scenes around betrothals, church patronage, and the public face of rule give her agency beyond the private sphere. Beecham’s Edith plays the domestic stakes without dimming the political ones; choices at the hearth ripple into the hall.

As for the big historical beats, the show signals the Stamford Bridge prelude without turning it into a footnote. The Hardrada track sparks the sharpest debate: critics argue the portrait relies on grim tropes, undercutting a figure whose claim and tactics were more complex. That conversation is likely to grow as the season moves through the final stretch toward Hastings.

The direction favors clarity over chaos in battle scenes—formations, ground, and morale matter. In quieter episodes, the emphasis shifts to counsel and confession: characters test arguments in private, then bare the blade in public. Costuming and set design stick to grounded textures rather than polished pageantry, making royal rooms feel lived-in, not gilded for show.

Viewers who come for accuracy will find points to praise and to argue. The series nods to the “arrow in the eye” debate from the Bayeux Tapestry and resists a single answer, which suits the history. Where it simplifies—particularly around Edward’s agency—it does so to keep tension high and motives legible. Whether that trade-off works will depend on what you value more: fidelity to every footnote, or a narrative that keeps the pressure rising.

Right now, the verdict is split, reflected in that 5.9/10 IMDb score from 416 ratings. Praises cluster around scale, performances, and the way the show treats legitimacy as the real battleground. Critiques focus on compression—how eight hours can still feel tight when you’re juggling a coronation, multiple courts, and three claimants with decent cases.

For UK viewers, King & Conqueror airs on BBC One. With eight episodes, expect a weekly rhythm that builds toward the Hastings set piece and its personal fallout. The question the show keeps asking along the way isn’t just who wins, but who pays: families split by oaths, nobles betting their lands on a claim, and a country learning how quickly custom can become kindling when power changes hands.